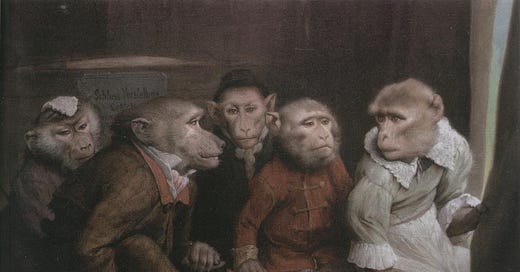

Header Image: Letzte Vorstellung (Last Performance), Gabriel von Max (1885).

Raju Bandar became a celebrity in Nainital in the late 2000s.

The monkey smoked, drank and chewed gum atop a Maruti 800 parked outside the Coronation Hotel. He would have swore too if he could, his vices cheered on by the idlers and curious passers-by swarming him.

‘Bandar’ was a misnomer, of course: for locals, a ‘bandar’ (or monkey) meant the red-faced macaque. Raju was a langur—a larger, grey-fur monkey with a black face and a long tail. ‘Raju Bandar’ just had a nice ring to it, so the name stuck. All townsfolk had opinions on him. Raju was the bravest of beasts, a neighbor would say. ‘Langurs are shy creatures, proper gentlemen compared to those red-faced devils. The little courage they can muster is spent stealing a fruit or two from people’s gardens. They keep to themselves otherwise, never bother people unless they bother them. Then this guy emerges out of nowhere and not only does he dare to befriend people, he also drinks and smokes with them! It’s incredible, all of it.’

Others thought he was a cautionary tale in the making: ‘Wait till he gets drunk and rips out a guy’s hair, or worse, a child’s face. Terrible parents, letting their kids wander near him. They’re waiting for some poor child to become his victim before he’s chased out of town,’ my fifth-grade teacher would lament.

‘He’s probably been trained to smuggle drugs up his you-know-what. A mule, you see. No wonder why he’s so comfortable around people,’ thought Sharad, a senior in tenth-grade who sat with us in the school van.

I had never seen Raju. Kids living at the lake’s upper shore saw him all the time, and they talked about him all the time. I didn’t get to go down to the shore regularly enough for me to glimpse him. Nainital looks like a leafy bowl: a ring of tall hills cup the lake below. My school was on the rim of this bowl; my home, halfway down another hilltop, not far away. On most days my life was spent shuttling between these two places. One only went downhill to the markets when something was absolutely needed: textbooks, notebooks, grocery, rations.

My classmates made Raju seem very grand, but also very human—a man almost, as if he was a traveler from a far away land, amused as he sampled the vices of this quaint, unknown town, surrounded by admirers. Coming from children, the descriptions were exaggerated, of course, but I’d taken to imagining him lounging in a chair, a charming man but for his grey fur and long tail, taking a deep drag from a cigarette some idler handed him, drinking from another man’s whisky glass, laughing at a joke someone cracked, shaking hands all around.

So when I saw him for the first time, I was underwhelmed. He was a lanky grey animal, all face and limbs with a vacant expression on his face, pulling a bit of his bubblegum out like string cheese before slurping it up and chomping on it again. My grand imaginings had disappointed me. Or perhaps it was my desire to see him smoke or drink, which I never did. Or did I? I’m unsure. I do remember seeing him one more time, in a cloud of smoke with a cigarette in his hand, but whether the sight was a true memory or a vividly imagined scene that stuck with me, I don’t know.

***

For years after, I’d think of Raju Bandar during idle moments: him along with Sunglasses, who thought that he had died long ago, and the figure veiled from head to toe in a black burqa, with the gait of a tank—a man deeply ashamed of his vitiligo, and the local ‘Yeti’, a poor, mentally unsound man with hypertrichosis, rumored to break rocks on his forehead and munch on nettles near the jungles of Naina Peak, the town’s highest point. Raju Bandar was one of these many strange beings that populated the town then, a quaint memory you’d smile at sometimes when you remembered your childhood.

Largely forgotten thus, he became the topic of a lively discussion in a small hotel room in Nainital about a decade later. I was in town on Christmas for a reunion with Pavan and some old friends, having started the practice only in 2020, when after years, fate brought me back to a place near my hometown.

I asked one of Pavan’s lawyer friends, Sohum, if he remembered Raju.

‘Oh, haven’t thought of him for years. Fun guy, wasn’t he? Haha. Giri da was heartbroken, of course. He thought of Raju like his son.’

‘Who’s Giri da?’

‘Lived only a short distance from here, down the steps. He’s no more. Loved animals. Even got into trouble with some forest rangers once because he found some tortoise lying belly-up on the road and took him home, and it turned out to be an endangered species. He could’ve been jailed for that, but it was an honest mistake, and the neighbors created too much of a ruckus and even called a journalist, so they backed off.’

‘How did Raju and Giri meet?’

‘Giri found Raju as an injured little cub crying beside a forest trail. Either some leopard had made a meal of his mother or an elder from a rival group had injured him. Giri da took him home, cleaned and bandaged his wounds, and then left him in a different part of the jungle again. Next morning, Raju was back at his doorstep.

‘He tried getting him to leave his house three times, and when he showed up the fourth time, Giri da gave up. He treated him like his grandson. All of us remember playing with him,’ people in the room nodded.

‘He even got his wife to weave sweaters for the guy, grew to be really fond of him. But then, teenage came. Raju grew rebellious. He wouldn’t even come home to eat his meals, and started hanging out with the loafers down the huge grilled drain. That was when the stunts started. They’d give him a shot of Old Monk for the laughs. Then they gave him whiskey, made him smoke. They didn’t force him or anything. The trick to make him do something was to do that thing but pretend to be secretive about it, as if you were excluding him from all the fun, and he took it up in an instant.

‘But the clowns overdid it one day, and Raju got home drunk. Giri da was incensed. Next day he followed Raju to the drain, and when he spotted the idlers, he chewed them out. “Raju wouldn’t go out from now on,” Giri da thundered, “shame on you for corrupting my boy!”

‘But Giri da, in his love, had forgotten that Raju was no boy. He kept shrieking to be let out day and night for a couple of days, and Giri da knew that Raju had to go when he struck a dinner plate off his wife’s hands and lunged at her. Giri da then caught him by the scruff of his neck and cast him out. Broke his heart to do that.

‘Raju would hang out with the idlers all day, and then return to Giri da’s house at night. Giri da threw his utensils at him, shooed him away. He had to do that half a dozen times more before Raju realized he wasn’t welcome anymore. That’s when he joined the idlers full time, and at night, when they went back to their homes, he took to bunking with the porters at the Mall Road. It worked for him splendidly: the porters always had some cheap alcohol they gave him every night.

‘Giri da died a few years back, heartbroken. His time with Raju was short, but it left a mark on him. He had no son of his own, and he had come to lavish all his affections on Raju alone. It feels very insensitive saying this, but it was entirely Giri da’s fault. What would a langur know about responsibility and love?’

I wanted to ask more about Raju, but then more of our friends began shuffling into the room. The conversation shifted to other interesting things, and everyone forgot about him.

I wonder what became of Raju. Perhaps he ran away one day. But hearing that his will hinged on alcohol, that seems unlikely. Short of an accident, only the most tragic end seems the most probable: Raju died a drunk, that miserable, twice-orphaned local spectacle, his tragedy unknown to the tens of thousands that had flocked to see him in his lifetime, unknown, perhaps, to even him.

This was an incredible read, Malay! It really felt like a tale, something woven from a special place. You had me the whole way.

In my local suburb there was a similar character... "The Dancing Man of Kew" - there's even videos of him on Youtube. He was enigmatic, appearing here and there all over the suburb, headphones in, laughing almost manically as he danced.

Everyone loved him. One evening as I ate dinner outisde a restaurant with my family he sat down with us, and was warmly welcomed. He's passed away now, but the shared memories between the people who grew up knowing him are still so fun to recall.

Thanks for this piece, it was really well written - I'm subscribing for the next ones!

This was an amazing read, Malay! Thanks for your comments on my posts which helped me find your work. We had our own version of the weird, hysteria-causing monkey in Old Delhi, Kala Bandar, although he was supposedly a menace. Really enjoyed seeing the Naini Lake, reminded me of the holidays we took up north when I was little.